95%

of felony convictions in the U.S. are obtained through guilty pleas

18%

of known exonerees pleaded guilty to crimes they didn't commit

65%

of 418 exonerees who pleaded guilty were people of color

83%

of DNA exoneration plea cases resulted in identification of the alternate perpetrator

WATCH THEIR STORIES

ANGELA GARCIA

18 YEARS AND COUNTING

RAYMOND TEMPEST

24 YEARS SERVED

Clay Chabot

24 YEARS SERVED

Leroy Harris

29 YEARS SERVED

Christopher Ochoa

13 YEARS SERVED

Brian Banks

5 YEARS SERVED

Ada Joann Taylor

19 YEARS SERVED

Rodney Roberts

18 YEARS SERVED

Innocent people are pleading guilty to crimes they did not commit. It happens to countless people each year, and there's no telling how many are behind bars as a result.

When most people learn that a person pleaded guilty to a crime, they believe the person must have done it. Yet, the number of wrongful convictions exposed over the last 25 years has proven that reasoning to often be unsubstantiated. In fact, nearly 11 percent of the nation's 362 DNA-based exonerations since 1989 involved people who pleaded guilty to serious crimes they didn't commit. Furthermore, according to the National Registry of Exonerations, 18 percent of known exonerees pleaded guilty.

While it's hard to believe that the United States criminal justice system could be so deeply flawed that innocent people are convicted of crimes they didn't commit, it's even harder to fathom that some of those innocent people actually felt compelled to plead guilty, often in exchange for a reduced sentence or to avoid the death penalty. When so many innocent people are agreeing to their own wrongful convictions, it's time to acknowledge that something is very wrong. The plea system is not a bargain; it's a problem that has no regard for innocence.

The guilty plea problem doesn't occur just at the front-end of the system. It also happens after people have taken the extraordinary step of demonstrating—through solid evidence and often decades in prison—that they were, in fact, innocent. People who have spent years fighting to both prove their innocence and to go home are faced with yet another impossible choice: go home immediately or much sooner without being exonerated or take the risk of being re-convicted at trial.

Instead of vacating their convictions on the basis of innocence, the prosecution offers the wrongly convicted a deal—plead guilty, have your sentenced reduced and go home. In some cases, the plea allows the defendant to still say they are innocent even while pleading guilty. Regardless, the system fails because it places resolving cases through pleas over uncovering the truth. It also denies wrongly convicted people the justice they deserve and burdens them with a criminal record and the severe collateral consequences that follow, including being denied jobs, housing, the ability to spend time with their children and the right to vote, as well as the lack of compensation for years wrongly served in jail.

We all are entitled to a criminal justice system that is fair, just and adheres to the Constitution's promise of a fair trial. And yet, we live with a broken system that no one deserves: prosecutors who threaten scared youth with harsh sentences, including the death penalty; incentives that make taking pleas over trial the most rational choice; overburdened and under-resourced public defense systems that can't provide adequate representation; and, judges who fail to serve as a check on the truth and justice. To makes matters worse, there's little incentive for challenging the status quo because, ultimately, plea deals keep an overburdened and dysfunctional system moving along. If every person charged with a crime demanded a trial, the system would be brought to a halt within a matter of hours. Sadly, our system relies on plea bargains.

There are no easy solutions to fixing this problem, but for the sake of the many innocent people trapped by a broken system, we must do something. The Innocence Project and 56 members of the Innocence Network across the country are committed to raising awareness about the over-reliance on guilty pleas at every stage of the system.

But change only comes when the public demands it. We invite you to join our campaign to fix America's guilty plea problem. Help us spread the word about this injustice and know that we will call on you when we need you to contact your lawmakers and demand change. We all need to work together to protect the innocent who are trapped in an overwhelmed and broken system.

JOIN THE MOVEMENT

Join us in preventing innocent people from pleading guilty to crimes they did not commit.

If you have previously subscribed to email or text notifications, your status will not be changed.

YOU'RE SIGNED UP!

Thank you for joining the cause to help this campaign grow even more, please spread the word to your friends and colleagues.

Invalid

SHARE YOUR STORY

Did you plead guilty to a crime you didn't commit? We'd like to hear from you.

The Innocence Project is a national litigation/public policy organization dedicated to exonerating wrongfully convicted individuals through DNA testing, and reforming the criminal justice system to prevent future injustice.

Invite an exoneree to speak at your next event. Learn More.

CLAY CHABOT

24 YEARS SERVED

In 1986, Clay Chabot was convicted of rape and murder based largely on his brother-in-law's testimony. Chabot's conviction was vacated in 2008 after new DNA test results proved that his brother-in-law had actually committed the crime. But despite this clear evidence of Chabot's innocence, the state indicated it may retry him. Instead of risking a new trial, Chabot accepted a guilty plea and was sentenced to time served.

See the full storyInvite an exoneree to speak at your next event. Learn More.

Invite an exoneree to speak at your next event. Learn More.

RAYMOND TEMPEST

24 YEARS SERVED

Raymond Tempest was convicted of second-degree murder in 1992. In 2015, the Rhode Island Supreme Court reversed Tempest's conviction because police and prosecutors failed to disclose evidence that supported his innocence. Although the state had no credible evidence against Tempest, prosecutors planned to retry him for the crime. Rather than face a new trial, Tempest accepted an Alford plea in exchange for his freedom.

See the full storyInvite an exoneree to speak at your next event. Learn More.

Invite an exoneree to speak at your next event. Learn More.

LEROY HARRIS

29 YEARS SERVED

Leroy Harris was convicted of robbery and sexual assault in 1989 based on serious prosecutorial misconduct and unreliable eyewitness identification. In 2017, despite new evidence—including exculpatory DNA test results—that strongly suggests Harris didn't commit the crime, prosecutors refused to vacate his conviction and instead offered him a plea deal. While the sexual assault charge against Harris was dismissed, he agreed to enter Alford pleas to the remaining charges to regain his freedom.

See the full storyInvite an exoneree to speak at your next event. Learn More.

Invite an exoneree to speak at your next event. Learn More.

ANGELA GARCIA

18 YEARS AND COUNTING

In 2001, Angela Garcia was convicted of a 1999 house fire that killed her two daughters. Garcia's conviction rested on circumstantial evidence and a flawed arson investigation—a forensic discipline that's been scrutinized in recent years for lacking scientific validity. In 2016, on the eve of the hearing where Garcia planned to present evidence that she was entitled to a new trial, prosecutors agreed to a greatly reduced sentence in exchange for a plea.

See the full storyInvite an exoneree to speak at your next event. Learn More.

Invite an exoneree to speak at your next event. Learn More.

Christopher Ochoa

13 YEARS SERVED

Chris Ochoa pleaded guilty to the 1988 murder of Nancy DePriest, implicating his roommate, Richard Danziger, in the process. It was later discovered that Chris' confession was coerced and that neither man had anything to do with the crime.

See the full storyInvite an exoneree to speak at your next event. Learn More.

Invite an exoneree to speak at your next event. Learn More.

Ada JoAnn Taylor

19 YEARS SERVED

JoAnn Taylor was one of six people convicted of raping and killing a 68-year-old woman in Beatrice, Nebraska. She agreed with prosecutors to plead guilty and testify at the trial of co-defendant Joseph White about her alleged role in the murder. In exchange for her testimony, she was sentenced to 10 to 40 years in prison. She was exonerated in 2009 after spending 19 years in prison for a crime she didn't commit and has since been compensated with her co-defendants, now known as the "Beatrice Six."

See the full storyInvite an exoneree to speak at your next event. Learn More.

Invite an exoneree to speak at your next event. Learn More.

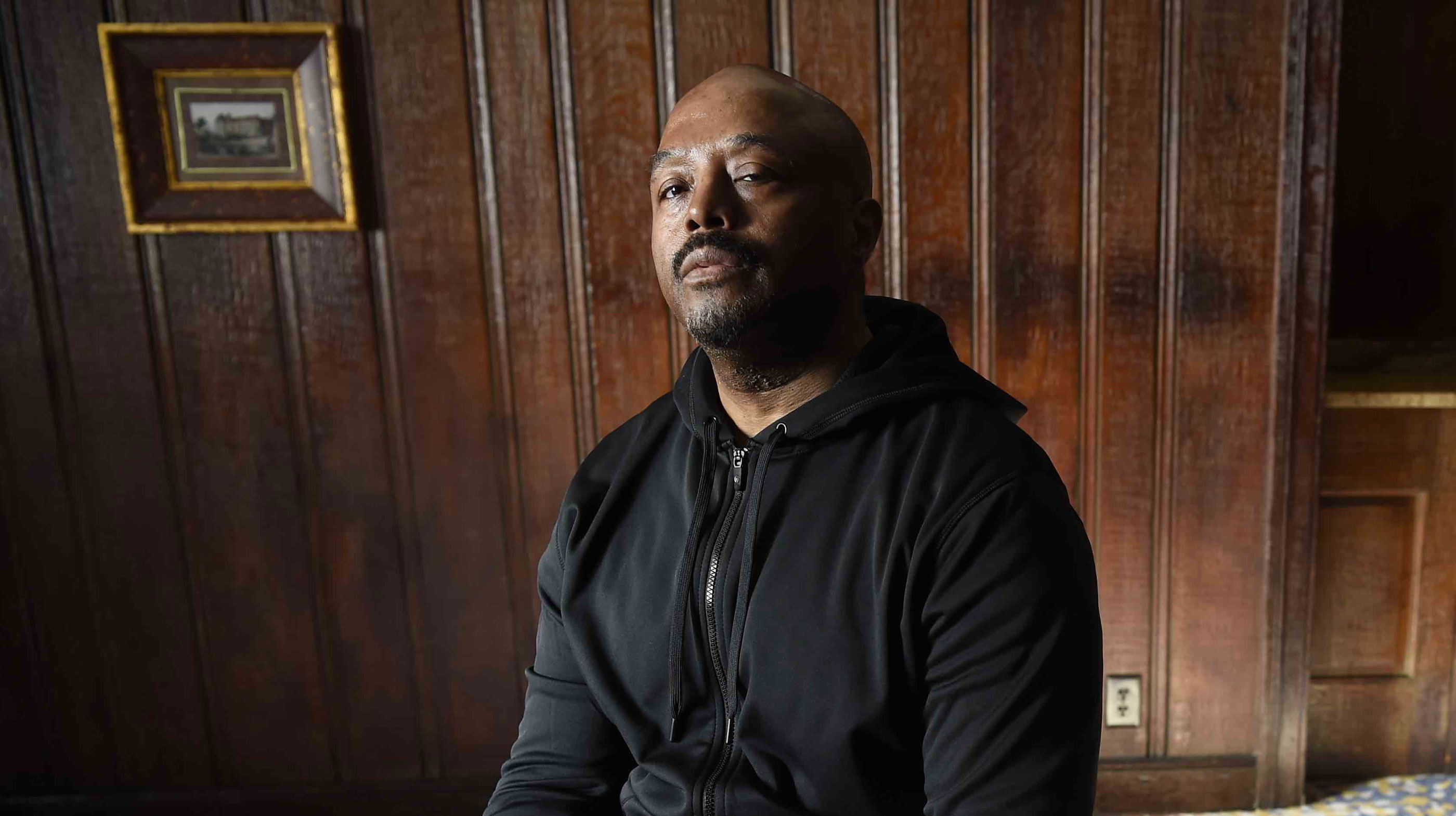

Rodney Roberts

18 YEARS SERVED

In 1996, Rodney Roberts was arrested for assault following a dispute with a friend. He was held in custody for a few days expecting release when he was arraigned for the kidnapping and sexual assault of a 17-year-old girl. The police said she had identified him in a photo array. Following the advice of his attorney, Roberts pleaded guilty to kidnapping to avoid a harsher sentence.

SEE THE FULL STORYInvite an exoneree to speak at your next event. Learn More.

Invite an exoneree to speak at your next event. Learn More.

Brian Banks

5 YEARS SERVED

Brian Banks was exonerated after his accuser contacted him on Facebook and admitted she had fabricated the entire story against him. He spent 5 years in prison for a crime he didn't commit and was exonerated in 2012 with the help of the California Innocence Project.

SEE THE FULL STORYInvite an exoneree to speak at your next event. Learn More.

Invite an exoneree to speak at your next event. Learn More.

Actor Hill Harper

Watch award-winning actor and Innocence Ambassador Hill Harper explain why America has a guilty plea problem. Join him in the fight to stop wrongful conviction.

Join the movementInvite an exoneree to speak at your next event. Learn More.

Invite an exoneree to speak at your next event. Learn More.

JUDGE JED RAKOFF

US District Judge Jed S. Rakoff is one of the leading experts on the guilty plea phenomenon. Watch him explain how the current state of the guilty plea system arose.

Join the movementInvite an exoneree to speak at your next event. Learn More.